Key Takeaways

- Dark matter makes up 27% of the universe but has never been directly detected

- Gamma-ray emissions from the Milky Way’s center could be proof of dark matter

- Two competing theories – dark matter collisions vs neutron stars – are equally likely

- New telescope in Chile could provide definitive answers by 2026

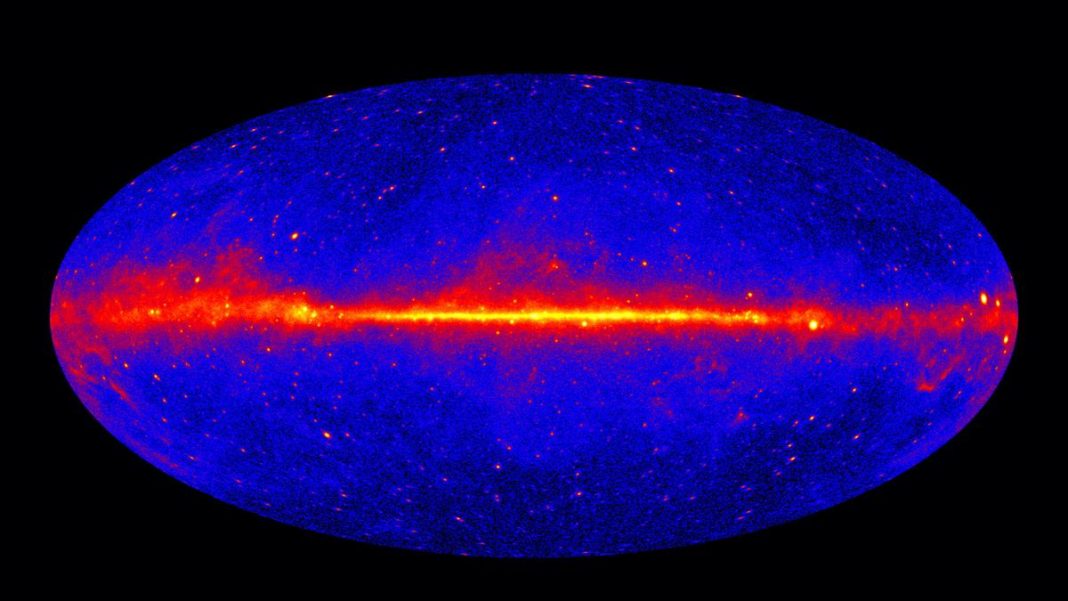

Scientists are closer than ever to confirming the existence of dark matter through analysis of mysterious gamma-ray emissions near our galaxy’s center. A comprehensive study published in Physical Review Letters reveals that dark matter particle collisions could explain the observed gamma-ray signals as well as the competing neutron star hypothesis.

The Cosmic Mystery of Dark Matter

Everything we can see in the universe – from stars and planets to everyday objects – constitutes only 5% of cosmic composition. Dark matter, which doesn’t absorb, reflect, or emit light, makes up about 27%, while dark energy accounts for the remaining 68%.

Scientists have long been confident about dark matter’s existence due to its gravitational effects, but direct proof has remained elusive. The Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope’s observations of excess gamma rays near the Milky Way’s heart now offer promising evidence.

Two Competing Explanations

Researchers have proposed two equally plausible theories for these gamma-ray emissions:

- Dark Matter Collisions: Dark matter particles congregating in the galactic center annihilate when they collide, generating gamma rays

- Millisecond Pulsars: Thousands of rapidly spinning neutron stars collectively emit the observed gamma radiation

Advanced simulations show both hypotheses could produce the exact gamma-ray signal detected by the Fermi satellite.

Scientific Breakthrough

“Understanding the nature of dark matter which pervades our galaxy and the entire universe is one of the greatest problems in physics,” said cosmologist Joseph Silk of Johns Hopkins University, co-author of the study.

“Our key new result is that dark matter fits the gamma-ray data at least as well as the rival neutron star hypothesis. We have increased the odds that dark matter has been indirectly detected,” Silk added.

Future Detection Prospects

The Cherenkov Telescope Array Observatory, currently under construction in Chile and expected to be operational by 2026, may finally resolve this cosmic mystery. As the world’s most powerful ground-based gamma-ray telescope, it could differentiate between emissions from dark matter collisions and neutron stars.

“Because dark matter doesn’t emit or block light, we can only detect it through its gravitational effects on visible matter. Despite decades of searching, no experiment has yet detected dark matter particles directly,” explained lead author Moorits Mihkel Muru of the University of Tartu.

The Galactic Context

The gamma-ray excess spans the innermost 7,000 light-years of our galaxy, approximately 26,000 light-years from Earth. Gamma rays represent the highest-energy waves in the electromagnetic spectrum, making them ideal for detecting high-energy cosmic events.

The Milky Way likely formed when a vast cloud of dark matter and ordinary matter collapsed under gravity. “The ordinary matter cooled down and fell into the central regions, dragging along some dark matter for the ride,” Silk explained.

While dark matter particles annihilating upon collision could produce the observed gamma rays, the collective emission from thousands of millisecond pulsars remains an equally compelling explanation, setting the stage for future cosmic discoveries.