Underwater ‘Storms’ Threaten Antarctica’s Doomsday Glacier, Study Reveals

Violent underwater storms are rapidly melting Antarctica’s Thwaites Glacier from below, potentially accelerating global sea level rise far beyond current projections, according to new research.

Key Takeaways

- Underwater vortexes contribute up to 20% of total melting in the region

- Thwaites Glacier collapse could raise sea levels by 1-2 meters (3-6 feet)

- Current climate models underestimate these storm-driven melting effects

- The process creates a vicious cycle of melting and turbulence

The Underwater Storm Phenomenon

Researchers from the University of California, Irvine discovered storm-like circulation patterns beneath Antarctic ice shelves that are aggressively melting both the Thwaites Glacier (nicknamed the Doomsday Glacier) and Pine Island Glacier.

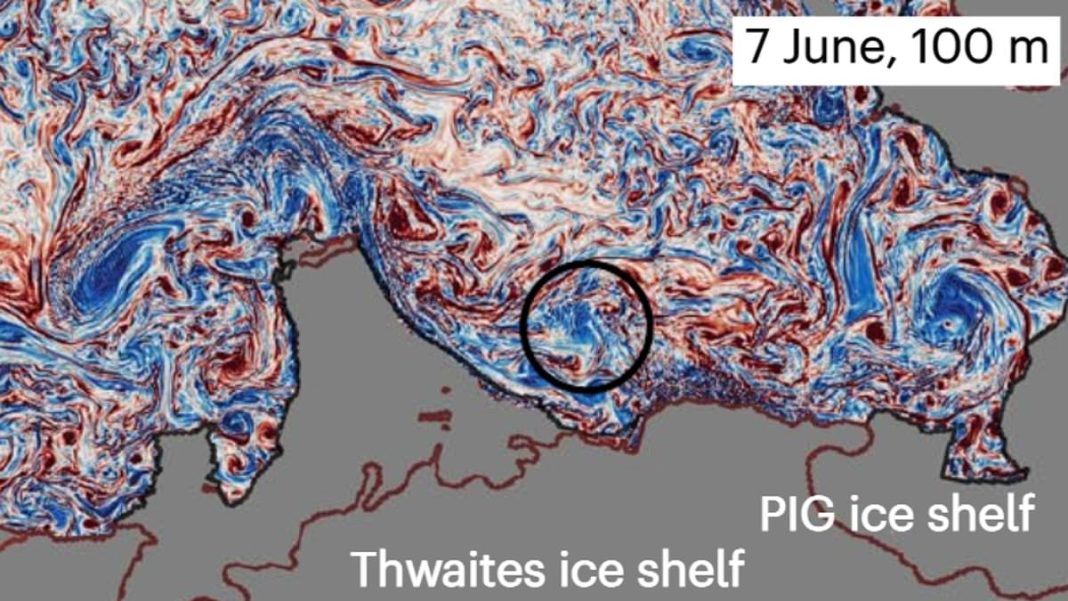

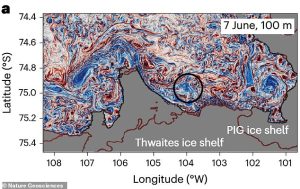

Study author Mattia Poinelli described the vortexes as “strongly energetic” and noted they “look exactly like a storm.”

“There is a very vertical and turbulent motion that happens near the surface,” Dr Poinelli told climate organization Grist. “In the future, where there is going to be more warm water, more melting, we’re going to probably see more of these effects in different areas of Antarctica.”

How the Underwater Storms Work

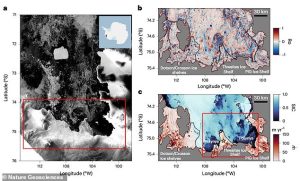

These swirling ocean currents, called “submesoscale” features, measure between 0.6 and 6.2 miles across. They form in the open ocean when waters of different temperatures collide, then travel toward Antarctica where they intrude glacier cavities and melt ice from below.

The storms create a dangerous feedback loop: they draw warmer water from ocean depths into glacier cavities while pushing away colder freshwater. More melting generates more turbulence, which causes additional melting.

“In the same way hurricanes and other large storms threaten vulnerable coastal regions around the world, submesoscale features in the open ocean propagate toward ice shelves to cause substantial damage,” said Dr Poinelli.

The Doomsday Glacier Threat

Thwaites Glacier spans 74,131 square miles – approximately the size of Great Britain – and is up to 4,000 meters thick. Its collapse alone could raise global sea levels by 1-2 meters (3-6 feet), with the potential for more than twice that amount if the entire West Antarctic Ice Sheet follows.

The glacier is particularly vulnerable because its interior lies more than two kilometers below sea level while its coastal base remains quite shallow.

Implications for Sea Level Projections

This discovery has major implications for climate modeling. Current projections may drastically underestimate future sea level rise because they don’t adequately account for these underwater storms.

“This underscores the necessity to incorporate these short-term, ‘weatherlike’ processes into climate models for more comprehensive and accurate projections of sea level rise,” Dr Poinelli emphasized.

The West Antarctic Ice Sheet, home to both Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers, contains enough ice to raise global sea levels by up to 3 meters (10 feet) if it completely collapses.

Future Outlook

While the exact timeline remains uncertain, researchers warn that greenhouse gas emissions have accelerated the process, making collapse a matter of centuries rather than millennia.

The study, published in Nature Geosciences, concludes that as climate warming continues, these underwater storm events will become increasingly frequent with “far-reaching implications for ice-shelf stability and global sea-level rise.”