Key Takeaways

- Toxic algae blooms in Florida linked to Alzheimer’s-like brain damage in dolphins

- Miami-Dade County has 10-15% higher Alzheimer’s rates than national average

- Neurotoxins from algae can accumulate in seafood and marine food chain

- Researchers call for urgent public health monitoring and exposure prevention

Scientists have uncovered alarming evidence that toxic algae in Florida’s waters may be contributing to Alzheimer’s disease. Research on stranded dolphins revealed brain damage strikingly similar to Alzheimer’s patients, linked to neurotoxins from harmful algal blooms.

Dolphin Brains Show Alzheimer’s Hallmarks

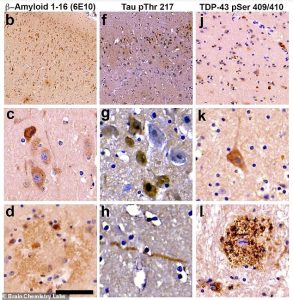

Researchers studying dolphins in Florida’s Indian River Lagoon discovered these marine mammals displayed brain changes identical to Alzheimer’s patients. The changes included misfolded proteins and plaques associated with cyanobacterial toxins from algal blooms.

Dr David Davis of the Miller School of Medicine told the Daily Mail: “Environmental factors may play a significant role in triggering or exacerbating neurological illnesses.”

He noted: “Miami-Dade County has one of the highest rates of Alzheimer’s in the US.” The region experienced severe algal blooms in 2020 that lasted months longer than typical events.

Alarming Statistics and Geographic Overlap

In 2024, approximately 77,000-80,000 people in Miami-Dade County were estimated to have Alzheimer’s – 10-15% above the national average.

“Maps of algal bloom occurrences and Alzheimer’s prevalence overlap in concerning ways,” Davis said. “We’re really worried about people in Florida being exposed.”

Dangerous Toxins in Algal Blooms

Florida has tracked harmful algal blooms since 1844, but climate change and environmental factors now fuel “super-blooms” lasting months. These blooms produce dangerous neurotoxins including:

- BMAA (β-N-methylamino-L-alanine)

- 2,4-Diaminobutyric acid (2,4-DAB)

- N-2-aminoethylglycine (AEG)

Guam Study Reveals Food Chain Risk

A separate study in Guam showed BMAA toxins entering the food chain through fruit bats that consumed toxic cycad seeds. Villagers who ate the bats developed ALS-PDC, a rare neurological disorder combining symptoms of ALS, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

Dr Paul Allen Cox’s research on cyanobacterial toxins initially faced skepticism but inspired the Florida studies. Davis confirmed: “The same toxins have been detected in the marine food web.”

Food Chain Accumulation and Human Risk

Once released into marine environments, these neurotoxins accumulate up the food chain, potentially reaching humans through contaminated seafood.

“Any exposure to these toxins is concerning,” Davis warned. “In Florida, doses are likely lower and spread over longer periods, but we don’t yet know the long-term effects on humans.”

Current Monitoring and Safety Measures

Researchers now closely monitor Florida’s waterways and seafood for cyanobacterial toxins. Testing includes:

- Regular sampling of fish, shellfish and aquaculture water

- Laboratory analysis using liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry

- Pre-market testing at fisheries and processing plants

- Random spot checks at restaurants and retail markets

When toxins are detected, harvest areas close until levels return to safe limits, ensuring contaminated seafood doesn’t reach consumers.

Critical Need for Long-Term Studies

Davis emphasized the importance of dolphin research: “[That] is why experimental models like dolphins are so important. They help us understand potential impacts on public health.”

He contrasted Florida’s exposure with Guam’s: “In Guam, people had a really high dose and developed the disease rapidly. Here, we’re probably looking at smaller doses over longer periods of time.”

With Miami-Dade facing both high Alzheimer’s rates and repeated algal blooms, Davis concluded: “Understanding and mitigating exposure is critical for protecting communities.”