In the early 2000s, as a cub reporter writing my first gig reviews, I worried all the time about getting the setlist wrong.

I would stand in the front row, notebook in hand, jotting down every track a band played, and praying silently in thanks each time an artist announced their next number.

The major bands weren’t much of a problem; one likely already knew their discography, and there was always a superfan around if one didn’t recognise a tune or two. But the unfamiliar acts, and (oh God) the independent bands, could mean hours of forensic digging.

Track down the band manager and hope they had a list; scour a fledgling internet hoping chat forums would hold clues. Get a single track wrong, and one risked having one’s credibility called into question (there are few media critics as brutal as music fandoms).

Today, such anxiety feels almost quaint.

Within minutes of a gig ending — sometimes before the encore confetti has had time to hit the floor — the entire list of songs performed has been uploaded to Setlist.fm. This free, Wikipedia-style platform has quietly become the world’s most comprehensive archive of live performance data.

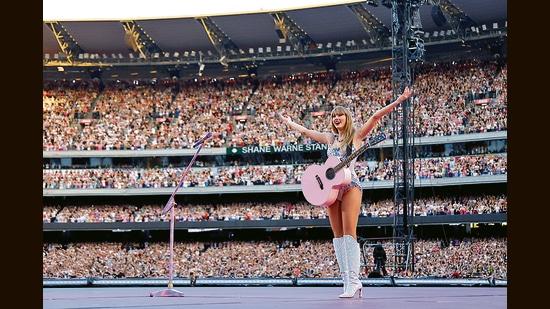

Created in 2008 by the Austrian media agency Molindo and powered by volunteers around the world, the website now hosts over 9.7 million setlists as performed by over 438,000 artists. With a few clicks, one can see what John Mayer performed at his Mumbai gig earlier this month; what Taylor Swift’s Eras songlists have looked like, over the course of that juggernaut of a tour. One can even go all the way to the back of the archive and see what Mozart, aged 11, played at a concert in Czechia in 1767 (Symphony No. 6 in F minor, apparently).

Quietly, the platform is now not just documenting but also shaping concert culture.

Fans are scrolling through setlists to decide which concerts to attend. Musicians, aware of this, are mixing in surprise songs and guest appearances, making an effort to preview new material, and burying sonic Easter eggs in shows, for the delight of the audience but also so these can show up on the setlists and elsewhere online.

The site has drawn enough attention that multinational events conglomerate Live Nation Entertainment acquired it in 2010 (the same year as its headline-grabbing merger with TicketMaster); though it only announced this two years later. “Setlist.fm fits perfectly with our goal of providing fans an engaging experience that extends the fun and excitement of the live concert before, during and after the show,” Live Nation CEO Michael Rapino said, in a statement in 2012.

The website is fairly simple: anyone can add or edit a setlist; a community of volunteer moderators verifies and refines entries. This kind of archival work was already being done, across different forums and fan websites; but it was necessarily scattered and haphazard.

Setlist.fm brought it all together, and added layers of moderation. It gave music nerds the tools to make the most of their data-obsessiveness.

Each time a list is uploaded, the system’s back-end also automatically checks the internet for song streams, YouTube videos and lyrics, and adds them to the page. In recent years, the site has begun posting analysis too: average concert start times; set lengths; most-oft-performed songs. Lately, an editorial section has been added, with photo galleries, trend stories, a blog and news from the world of music.

The number of users has ballooned from 1.5 million a month in 2012 to over 6.5 million a month today.

Along the way, it has become a platform for a distinct kind of obsession with music. Some fans pore over data to put together predictions of what an artist will play at their next show; others argue in the comments about which version of a B-side a band played during a show.

Fans even use past lists to decide, mid-concert, when might be the best time for a bathroom break.

TRACK RECORD

For music journalists and historians, Setlist.fm is the stuff of fantasy.

Details include lists of impromptu gigs, rare covers, songs performed for the first time in a certain number of years — just the kinds of details that can be incredibly difficult to find, or simply be lost to the ether.

It is also an evocative record of our bond with live performance.

Look up the oldest documented concert in Milwaukee and one encounters a pair of 1851 performances by the English soprano Anna Bishop. Analyse how the Rolling Stones setlists have evolved over six decades, and one sees genius in motion.

As with everything on the internet, there is a flip side.

Some have begun to grumble that the website saps some of the mystery from the live music experience. Too much is being captured and shared, they say. Among the sceptics is Roger Daltrey of The Who. In 2024, refusing to share his own setlist, he told Billboard magazine he “can’t stand it”. “There’s no surprises left with concerts these days, ’cause everybody wants to see the setlist,” he added. “I’m f–king sick of it. The internet’s ruined the live shows for me.”

As with everything on the internet, there is also research and informed opinion on the subject.

Knowing what song a band will perform may actually diminish the initial thrill of discovery, but it doesn’t make the song or performance any less transcendent, or the joy you feel when singing along any less real, Jeremy Davis, a professor of philosophy at University of Georgia, writes, in a 2023 guest essay titled What’s Wrong with Setlist.fm?, on the blog Aesthetics for Birds.

“Thinking about what (the artist) might play tells us very little about how the performance might unfold—for example, whether the band might play interesting renditions of familiar songs, the specifics of the stage performance, the band’s stage energy… and so on,” he points out. Any of these moments could become the memory of a lifetime; the viral moment of the year.

Yes, foreknowledge can subtly alter the aesthetic experience, he adds. The concert then becomes an exercise in confirmation, rather than discovery. The surprise is replaced by anticipation; the gasp becomes a countdown.

We should be aware of the ways a setlist risks compromising the very thing we seek to safeguard: The experience itself, Davis points out.

Would we want to go back, then, to the good old days when we didn’t know if we were walking into an hour-long greatest-hits set or a show so infuriating that it might spark a riot (as Guns N’ Roses did in Montreal in 1992)? Come on. Who are we kidding?