The chip that could cure blindness: Tiny device restores vision

Scientists have revealed that a tiny chip implanted in the eye can effectively restore vision loss. In a groundbreaking trial, patients with age-related macular degeneration (AMD) regained the ability to read using the pioneering device.

Key Takeaways

- 84% of trial participants showed clinically meaningful vision improvement

- Patients could read letters, numbers and words after losing complete sight

- The 2mm chip works with AR glasses to create artificial vision

- First device enabling reading through an eye that had lost its sight

Sheila Irvine, one of the first patients to receive the implant at Moorfields Eye Hospital, described the experience as “dead exciting.” She said, “It was dead exciting when I began seeing a letter.”

Study author Professor Mahi Muqit from University College London called this development a “new era” in artificial vision history. “Blind patients are actually able to have meaningful central vision restoration, which has never been done before,” he stated.

How the Vision Restoration System Works

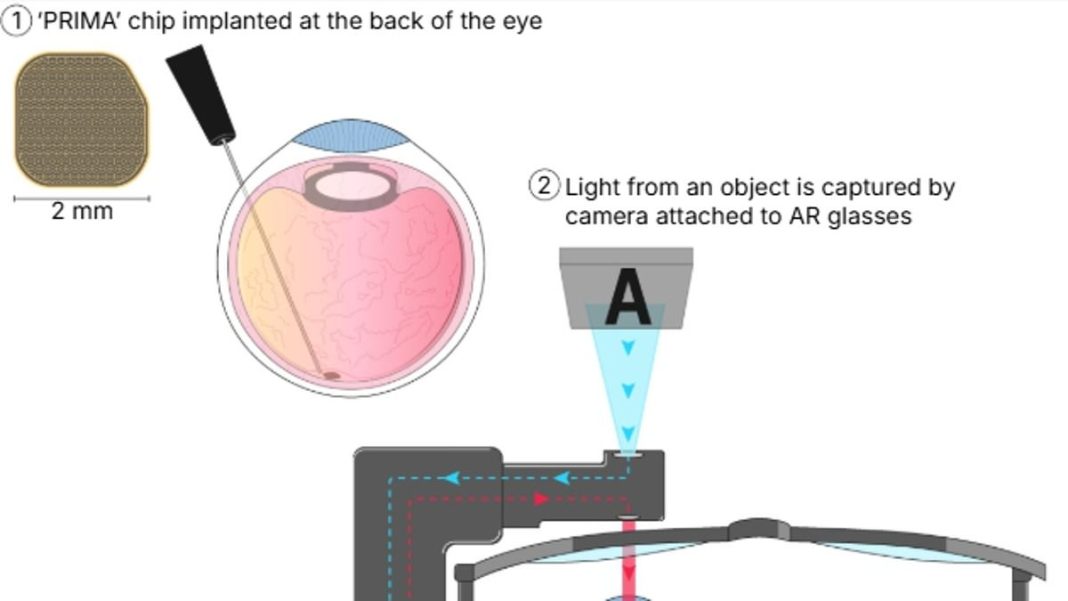

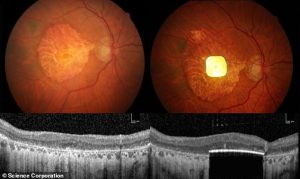

The chip, measuring just 2mm x 2mm and 0.03mm thick (half the width of a human hair), is implanted in the retina during a two-hour operation. Developed by Science Corporation, a California-based firm started by Max Hodak (co-founder of Neuralink with Elon Musk), the system works through an integrated process:

- Patients wear special AR glasses with a camera that detects light from objects

- Visual information transmits to a handheld computer that translates it into infrared patterns

- Infrared projects back through the glasses into the eye, hitting the retinal chip

- The chip converts infrared to electrical signals that travel to the brain as vision

- A zoom feature on the handheld computer allows magnification of letters

Clinical Trial Results

The international study involved 38 patients across 17 hospitals in five countries. All participants had lost complete sight due to AMD, where light-sensitive retinal cells deteriorate over years.

After approximately one month post-operation, patients began rehabilitation to train their eyes with the system. They practiced using the device through puzzles, crosswords, and even navigating the Paris Metro.

Remarkable results emerged one year later: 84% of participants (27 out of 32) showed clinically meaningful improvement in visual acuity. Those treated could read an average of five lines on a vision chart – some couldn’t see the chart at all before surgery.

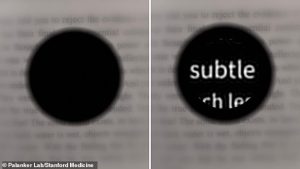

Ms Irvine described life with AMD as “like having two black discs in my eyes.” She added, “I was an avid bookworm, and I wanted that back. There was no pain during the operation, but you’re still aware of what’s happening.”

Medical Significance and Future Applications

Currently, no licensed treatment exists for dry AMD, the most common form that causes severe central vision loss. The findings, published in The New England Journal of Medicine, could pave the way for regulatory approval.

While the team acknowledges potential adverse effects like retinal detachment and ocular hypertension, they conclude that “the benefits of the PRIMA system outweighed the risks of implantation.”

Professor Muqit emphasized the life-changing impact: “These are elderly patients who were no longer able to read, write or recognise faces due to lost vision. They’ve gone from being in darkness to being able to start using their vision again.”

The restoration of reading ability represents a major improvement in quality of life, mood, confidence, and independence for patients who had lost hope of ever seeing again.

Understanding Age-Related Macular Degeneration

AMD is a painless eye condition causing gradual central vision loss. As the most common cause of visual impairment in the UK and US, it affects approximately 600,000 UK adults and nearly two million Americans.

The condition blurs central vision, making reading and facial recognition difficult. While it doesn’t cause total blindness, it significantly impacts daily activities. AMD occurs when the macula – responsible for central vision – stops functioning effectively.

Risk factors include aging, smoking, and genetic predisposition. The condition typically affects both eyes, though progression rates may differ between eyes.